Soviet RPG-7

|

The RPG-7 (Ruchnoy Protivotankovyy Granatomyot) is one of the most recognizable infantry weapons of the Cold War and remains in widespread use more than six decades after its introduction. It was formally adopted by the Soviet Army in 1961, building on lessons learned from earlier systems such as the RPG-2 and wartime German designs like the Panzerfaust.

The Soviet Union wanted a simple, rugged, inexpensive, and highly effective anti-armor weapon that could be used by conscript soldiers with minimal training. The RPG-7 met these requirements through a clever combination of:

- A reusable launcher

- Fin-stabilized, rocket-assisted grenades

- A simple optical sight

- Extremely tolerant manufacturing standards

Production was spread across multiple Soviet industrial facilities, including KMZ (Kovrov Mechanical Plant) and others within the USSR’s defense-industrial base. By the early 1970s when this example was manufactured the RPG-7 had already become standard issue across Warsaw Pact forces and was being exported globally.

|

Unlike disposable systems, the RPG-7 was designed for long-term service, allowing a single launcher to fire many types of munitions over its lifetime. This adaptability ensured relevance as armor technology evolved.

Soviet doctrine envisioned the RPG-7 as:

- A platoon- and squad-level anti-armor weapon

- A multi-role system for engaging vehicles, fortifications, and infantry

- A key enabler for light infantry facing mechanized forces

Its effectiveness did not rely on cutting-edge technology but on accessibility, volume, and tactical flexibility, a philosophy that proved enormously influential.

|

The RPG-7 became one of the most widely distributed weapons in history. Licensed and unlicensed production occurred in dozens of countries, including:

- China

- Egypt

- Romania

- Bulgaria

- Iraq

- Pakistan

- Iran

- North Korea

By the end of the Cold War, millions of launchers and tens of millions of rounds were in circulation. Large stocks remained after the collapse of the Soviet Union, often unsecured, making the RPG-7 readily available to insurgent and non-state actors.

|

Following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, RPG-7s rapidly became a signature weapon of insurgent groups. They were commonly employed by:

- Former Iraqi military personnel

- Sunni insurgent groups

- Shia militias

- Foreign fighters

In Iraq, RPG-7s were most often used not as pure anti-tank weapons, but as:

- Ambush weapons against convoys

- Area-denial tools in urban terrain

- Psychological weapons to disrupt patrols

RPG teams frequently targeted:

- Up armored HMMWVs

- MRAPs

- Light armored vehicles

- Fixed positions in FOBs such as Q-36 Radar positions and entry control points

While modern U.S. armor generally resisted penetration, RPG impacts often caused:

- Mobility kills

- Sensor damage

- Crew injuries from spall or blast effects

- Significant tactical disruption

|

One of the most consequential characteristics of the RPG-7 system and a major reason for its longevity and global spread is the high degree of interchangeability among launchers and projectiles manufactured by different countries. This interoperability was not accidental; it was a direct outcome of Soviet design philosophy and export strategy during the Cold War.

|

From its inception, the RPG-7 was engineered with generous tolerances and simple mechanical interfaces. The Soviet Union anticipated:

- Mass production across multiple factories

- Wartime repair in austere environments

- Export to allied states with varying industrial standards

As a result, the launcher’s key interfaces particularly the breech, venturi alignment, and projectile mounting standardized early and remained largely unchanged throughout the weapon’s service life.

|

During the Cold War, the USSR licensed RPG-7 production to numerous allies. These agreements typically required:

- Adherence to Soviet dimensional standards

- Compatibility with Soviet-produced ammunition

- Use of metric-based tolerances

Countries such as Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, and East Germany produced launchers and projectiles that were intentionally interoperable with Soviet originals. This ensured logistical flexibility within Warsaw Pact forces and simplified resupply in coalition operations.

|

The People’s Republic of China began producing RPG-7 variants (commonly known in the West as the Type 69) beginning in the late 1960s. While officially a “derivative,” Chinese engineers largely preserved the Soviet interface standards.

As a result:

- Chinese-manufactured projectiles were generally dimensionally compatible with Soviet launchers

- Soviet-made launchers could accept Chinese rounds, and vice versa

- Minor variations existed in materials, propellant formulation, and quality control, but mechanical fit was usually maintained

This compatibility proved decisive decades later, as Chinese-produced ammunition became widespread across the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia.

|

After 1991, enormous quantities of RPG-7 components entered unregulated markets. In many conflict zones especially Iraq and Afghanistan it was common to encounter:

- Soviet-era launchers paired with Chinese, Iranian, Egyptian, or Pakistani projectiles

- Mixed lots of ammunition from multiple countries used interchangeably

- Launchers with decades of service history firing non-original munitions

|

From a historical perspective, this interoperability allowed insurgent forces to maintain RPG capability despite fragmented supply chains. A launcher manufactured in the USSR in the early 1970s, such as those produced by KMZ, could remain operational for decades using ammunition from entirely different production lines and countries.The RPG-7’s cross national interoperability such as Chinese projectiles mated to Soviet manufactured launchers is not an anomaly but a defining feature of the system. It reflects a Cold War era design philosophy that prioritized simplicity, durability, and standardization over technological sophistication.

This characteristic explains why RPG-7s manufactured in the early 1970s remain functional and relevant today, and why the system continues to appear in conflicts long after the geopolitical order that created it has vanished.

|

Above: The markings on this RPG-7 show it to be manufactured in 1972 by the Kovrov Number 575 Machinery Plant (KMZ) in Soviet Russia. The circle and arrow symbol is specific to the KMZ Plant.

|

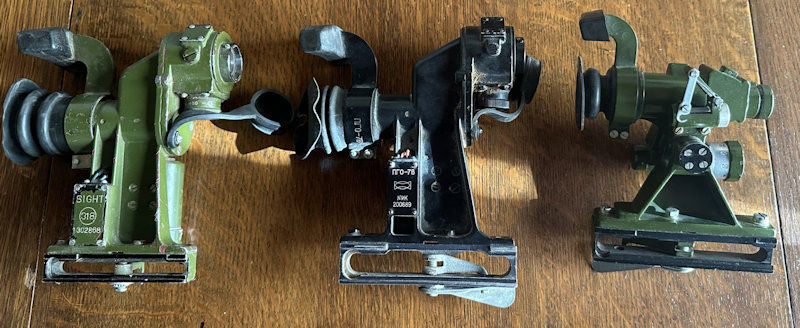

Above & Below Left: Chinese RPG-7 (Type-69) sight with a dissimilar size mount than this RPG-7 used in Iraq

Above & Below - Center: USSR RPG-7 sight typical for this Soviet RPG-7 used by Iraq

Above & Below Right: Chinese RPG-7 (Type-7) sight that fits the Soviet RPG-7 used by Iraq

|

Below: The Russian RPG-7 Optical Sight mounted on the launcher

|

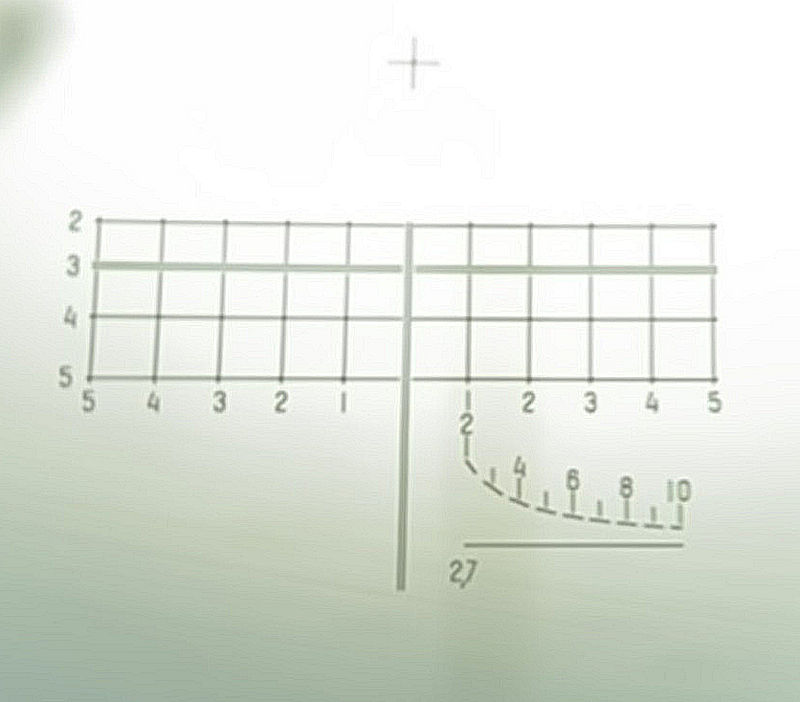

Below: The Russian RPG-7 Optical Sight recital pattern

|

Below: The Chinese RPG-7 Optical Sight mounted on the launcher

|

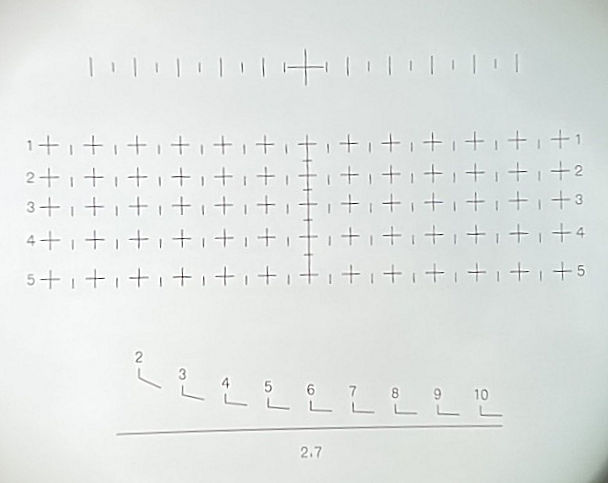

Below: The Chinese RPG-7 (Type-69) Optical Sight recital pattern

|

Below: A North Korean made bag with an Arabic-Indic painted marking for the number “3”. This example is for the gunner to carry. There are pockets for two RPG-7 projectiles and fin/boosters

|

Below: A North Korean made bag with an Arabic-Indic painted marking for the number “3”. This example is for the gunner to carry. There are pockets for two RPG-7 projectiles and fin/boosters

|

Below: A North Korean made bag open. This example is for the gunner to carry. There are pockets for two RPG-7 projectiles and fin/boosters

|

Below: The back of a North Korean made bag. This example is for the gunner to carry. There are pockets for two RPG-7 projectiles and fin/boosters

|

Below: A Bulgarian cardboard cylinder to carry the fins and booster for the RPG-7 projectile

|